Categories: Capabilities | SPA Fellows

Putting Force Design First – Logically

Author: LtCol Noel Williams, USMC (Ret), SPA Fellow for USMC Strategy, Policy, and Force Development

In a time of accelerating threats and rapid technological shifts, the U.S. military should reconsider how it approaches force design in its modernization process. Force design represents the logical first step in force modernization—and it should be performed concurrently with development and employment, not sequentially as current doctrine suggests.

Force design is not merely a checklist or a bureaucratic formality. It is a creative, systems-level process—a way to build a coherent, threat-informed force capable of fighting and winning future wars. As I argued in my Marine Corps Gazette article, “design is first and foremost an act of creation.” To prepare for the challenges ahead, the Joint Force would benefit from professionalizing this function, rethinking its doctrine, and aligning its organizations accordingly.

What Is Force Design—And How Is It Currently Positioned?

The Joint Staff defines force design in CJCSI 3030.01A as “a process of innovation through concept development, experimentation, prototyping, research, analysis, wargaming, and other applications of technology and methods to envision a future joint force.” The Marine Corps has embraced this concept since 2019, treating design as a centerpiece of transformation under the 38th Commandant. But across the broader Department of Defense, force design is often treated as a phase that follows current operations and precedes acquisition, positioned years in the future.

This positioning is problematic. Design should logically lead development and employment, just as an architect precedes a builder and occupant. The current CJCSI 3030.01A describes three timeframes:

While any process naturally takes time, these artificial time horizons can be counterproductive.

The Russo-Ukraine war has demonstrated that such a time-specific process cannot work effectively. Forces must be designed and redesigned in important ways in the near future, and the inability of a force to do so means defeat. Today’s security environment demands near-term force redesign to keep pace with peer adversaries. That makes force design a continuous task rather than a distant, one-time event.

A Critical Distinction: Concept-Driven vs. Threat-Based Planning

Calling out distinctions between concept-informed/concept-driven and threat-based/threat-informed may seem overly pedantic, but these distinctions have significance beyond semantic nitpicks. The shift to capabilities-based planning (CBP) in the early 2000s under Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld replaced threat-based design with a model that treated enemies as abstract sets of technologies without connection to geography, culture, or fighting methodology.

This approach encouraged military planning to shift focus inward rather than on the enemy, allowing institutional preferences to prevail over war-winning imperatives. The result was a force modernization effort that focused on refining legacy systems (e.g., better tactical aircraft and towed artillery) instead of developing more innovative capabilities like uncrewed systems, loitering munitions, or agile command-and-control networks.

The most important contribution of the 2018 National Defense Strategy was the unequivocal shift back to threat-based planning. Subsequent joint doctrine made improvements to how the Department approaches planning, requirements development, and solutions development. Yet adjustments must continue given the changing nature of threats, technologies, budgets, and strategies.

Shift the Sequence: From Time-Based to Logic-Based Design

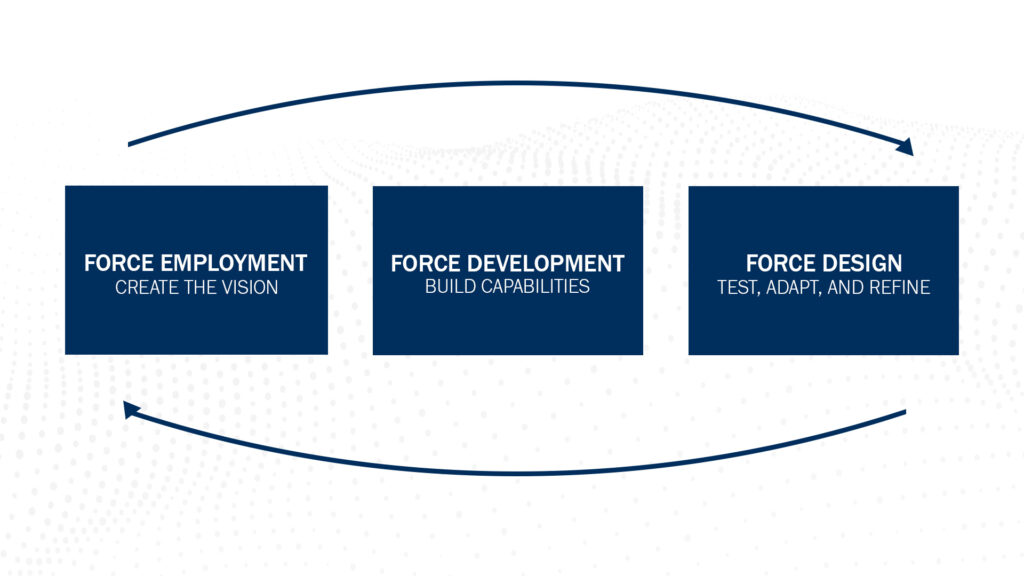

Current doctrine divides force planning into three distinct timeframes, with Force Design positioned farthest in the future. This sequencing implies that design occurs mainly in the distant timeframe. But in reality, the logical sequence should be:

It is critical that designers, developers, and operators maintain a continuous dialog to ensure healthy feedback loops for rapid adjustment to processes and plans. The current time-dependent characterization serves as an implicit segmentation that discourages interactions among these groups and thus compromises essential feedback.

Forward-deployed commanders and operating forces are increasingly conversant in both current and future adversary capabilities. When they ask for capabilities to counter existing and near-term adversary threats, they are often asking for capabilities far in advance of what’s currently planned in the acquisition pipeline.

Vision First, Not Concepts First

CJCSI 3003.01A states, “Concept-driven, threat-informed, capability development begins with a vision of the future operating environment that guides the DOD through a campaign of learning to identify the capabilities required to achieve the objectives established in national strategic guidance.”

However, concepts should not be the primary driver. Force Design should be concept-informed rather than concept-driven. Vision—a hypothesis about the desired attributes of the future force needed to solve a specific military problem—should come first. As Einstein said, “If I had an hour to solve a problem and my life depended on the solution, I would spend the first 55 minutes determining the proper question to ask.”

Concepts are useful because they pull together desired attributes into a coherent whole, but they are of varying quality and utility. Deconstructing concepts to transliterate them from conceptual think pieces to mechanistic lists, and then converting these lists to gaps and requirements, is likely to lead to confusion as the logical structure of force design is removed from the process.

An architect does not take a pile of materials and build a house from what is in the pile. Similarly, force designers should not simply compile lists from concepts without maintaining the systems perspective that makes those concepts meaningful.

Watch: Noel Williams, SPA Fellow for USMC Strategy, Policy, and Force Development interview

Force Design Requires Professionals

Currently, the Marine Corps’ combat development organization (CD&I) lacks dedicated force designers and instead relies upon ad hoc process teams, study groups, and organizational reviews. The initial planning for Force Design 2030 was performed by an ad hoc group known as Provident Stare. When this work was handed off to the Deputy Commandant CD&I, they had to proceed with a continuing series of integrated product team efforts focused on pieces of the overarching design. This approach structurally exposes the process to discontinuities and confusion given the lack of continuity.

The Army has addressed this challenge by creating a force management occupational specialty (FA 50) and establishing a Futures Command headed by a four-star general. The Marine Corps could consider a similar approach by converting existing capability portfolio managers (CPMs)—active-duty colonels—to force designers

These force designers would work together as an integrated team, with research, seminars, and supporting analysis culminating in the development of a blueprint for the Objective Force. Their routine would include regular briefings on concepts, guest speakers from academic and military institutions, and travel to exercises, experiments, wargames, and industry partners.

Align Development and Solutions with Design

Once the blueprint is established, force developers (who could be redesignated from deputy CPMs) would translate the vision into detailed requirements or problem statements. These should be directly aligned with the design portfolios.

Force developers would focus exclusively on requirements and problem statement development. Solutions would best be accomplished by solution developers under a single roof to benefit from multi-disciplinary expertise. Force developers would work in close coordination with solution developers to continually refine requirements while benefiting from the creative tension caused by the clear separation of responsibilities.

A Call to Evolve Doctrine, Culture, and Capability

The Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System (JCIDS) should be benchmarked against real-world conflicts like the Russo-Ukrainian War and its ability to deliver capabilities as defined by operational commanders. If it cannot deliver against these tests at the speed of relevance, it should be reconsidered.

"Force design is not about producing another list. It's about building a system—based on threats, refined through vision, informed by concepts, and tested through warfighting logic. It forms the foundation of modernization and should be treated as such in our doctrine and processes."

LtCol Noel Williams, USMC (Ret), SPA's Fellow for USMC Strategy, Policy, and Force Development

Conclusion: Make the First Thing First

Force design is where innovation and force modernization begin. It should become a permanent, professionalized, and prioritized discipline across all Services. The traditional incremental approach to force development worked in an era of incremental change, but the increasing complexity of the modern battlefield requires a more sophisticated approach.

Force design is the locus of innovation and the architect of force development; we should evolve our processes and organization and professionalize the force design workforce to do it effectively.

Read Noel’s previous post, “Shaping the Future of Force Design and Structure in an Era of Rapid Technological Change”

Related Posts

We invite you to subscribe and stay informed. Never miss an update as we continue providing the rigorous insights and expert analysis you rely upon to protect and advance our national security.